History of Germany (1945–1990)

| History of Germany | |

|---|---|

This article is part of a series |

|

| Early History | |

| Germanic peoples | |

| Migration Period | |

| Frankish Empire | |

| Medieval Germany | |

| East Francia | |

| Kingdom of Germany | |

| Holy Roman Empire | |

| Eastward settlement | |

| Early Modern period | |

| Sectionalism | |

| 18th century | |

| Kingdom of Prussia | |

| Unification of Germany | |

| Confederation of the Rhine | |

| German Confederation & Zollverein | |

| German Revolutions of 1848 | |

| North German Confederation | |

| The German Reich | |

| German Empire | |

| World War I | |

| Weimar Republic Saar, Danzig, Memel, Austria, Sudeten |

|

| Nazi Germany | |

| World War II Flensburg government |

|

| Germany since 1945 | |

| Occupation + Ostgebiete | |

| Expulsion of Germans | |

| FRG, Saar & GDR | |

| German reunification | |

| reunified Germany | |

| Topics | |

| Military history of Germany | |

| Territorial changes of Germany | |

| Timeline of German history | |

|

Germany Portal |

As a consequence of Germany's defeat in World War II and the onset of the Cold War, the country was split between the two global blocs in the East and West, a period known as the division of Germany. Two states emerged; West Germany was a parliamentary democracy, a NATO member, a founding member of what since became the European Union and one of the world's largest economies, while East Germany was a totalitarian Stalinist dictatorship allied with the Soviet Union, widely considered to be a Soviet satellite state. Germany would not be reunited until 1990, following the collapse of the East German communist regime.

The division of Germany

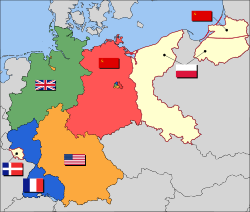

Four occupation zones

At the Potsdam Conference (July 16 to August 2, 1945), after Germany's unconditional surrender on 8 May 1945,[1] the Allies divided what was then determined to be "Occupation Zone Germany" into four military occupation zones – French in the southwest, British in the northwest, United States in the south, and Soviet in the east. Earlier maps and plans showed the Soviet Occupation Zone of Germany to incorporate the area of what became the Potsdam approved final Soviet Zone PLUS all of the 1937 German territory east of the Oder-Neisse Line. Austria, the occupied territory of Czechoslovakia, and the territories annexed to Germany during the war were now also detached. The Potsdam Agreement also formally removed the German provinces east of the Oder-Neisse line, within the 1937 boundary of Germany, (East Prussia, Eastern Pomerania and Silesia -- See Recovered Territories) from the pre-Potsdam unofficial Soviet Zone of Occupation and placed most of those territories under the administration of Poland, pending the final Peace Treaty (which turned out to be not forthcoming). The northerly part of East Prussia was placed under Soviet administration by the Potsdam Agreement. The Potsdam sanctioned administrative assignment of various eastern German territories to Poland and the Soviet Union ultimately had the effect of shifting "Germany" westward. Roughly 15 million ethnic Germans suffered terrible hardships in the years 1944 to 1947 during the flight and expulsion from the eastern German territories, the Nazi-occupied Poland and Czechoslovakia (the Sudetenland).

Of the roughly 12.4 million Germans, who in 1944 were living in territory that, following the dismembering of Germany, would become part of post-war Poland and Soviet Union, an estimated 6 million fled or were evacuated before the advance of the Red Army. Of the remainder up to 1.1 million died, 3.6 million were expelled by the Poles, one million declared themselves to be Poles, and 300,000 remained in Poland as Germans. Thousands starved and froze to death while being expelled in slow and ill-equipped trains. The part of East Prussia around Königsberg was administratively assigned by the Potsdam Agreement to the Soviet Union, and was "eventually" (actually, in a very brief de facto fashion) annexed by the Soviet Union.

The Potsdam Conference of July 16 to August 2, 1945, authorized by the Allies, sanctioned the "orderly and humane" transfer from their countries of those deemed by authorities in Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Hungary to be "ethnic Germans". At the same time the Potsdam Agreement also recognized that those expulsions were already in substantial progress and were putting a burden upon authorities in the German Occupation Zones, to include the abbreviated Soviet Occupation Zone created by the August 2, 1945 Potsdam Declaration. The main flow of German expellees at that time was from Czechoslovakia and Poland (to include the assigned Administrative Territories of most of Eastern Germany beyond the Oder-Neisse Line). The following is from the August 2, 1945 dated Potsdam Declaration: "Since the influx of a large number of Germans into Germany would increase the burden already resting on the occupying authorities, they consider that the Allied Control Council in Germany should in the first instance examine the problem with special regard to the question of the equitable distribution of these Germans among the several zones of occupation. They are accordingly instructing their respective representatives on the control council to report to their Governments as soon as possible the extent to which such persons have already entered Germany from Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, and to submit an estimate of the time and rate at which further transfers could be carried out, having regard to the present situation in Germany. The Czechoslovak Government, the Polish Provisional Government and the control council in Hungary are at the same time being informed of the above and are being requested meanwhile to suspend further expulsions pending the examination by the Governments concerned of the report from their representatives on the control council."

Many of the remaining Germans (especially those subject to Polish and Czechoslovakian authorities), and who were mainly women and children, were subject to severe acts of mistreatment, until finally deported to Germany in the 1950s. They were forced to wear identifying armbands and thousands died in forced labor camps such as Lambinowice, Zgoda labour camp, Central Labour Camp Potulice, Central Labour Camp Jaworzno, Glaz, Milecin, Gronowo, and Sikawa.[1] In addition, 2–2.5 million died as a result of ill-organised German evacuation, bombing, sinking of refugee ships, of hunger and deprivation during long marches in bitter cold, in the expulsion trains, in resettlement camps, or murdered by rampaging troops or populace. Another 165,000 were transported by the Soviets to Siberia.

The intended governing body of Germany was called the Allied Control Council. The commanders-in-chief exercised supreme authority in their respective zones and acted in concert on questions affecting the whole country. Berlin, which lay in the Soviet (eastern) sector, was also divided into four sectors with the Western sectors later becoming West Berlin and the Soviet sector becoming East Berlin, capital of East Germany.

.svg.png)

A key item in the occupiers' agenda was denazification; toward this end, the swastika and other outward symbols of the Nazi regime were banned, and a Provisional Civil Ensign was established as a temporary German flag; the latter remained the official flag of the country (necessary for reasons of international law as German ships had to carry some sort of identifying marker) until East Germany and West Germany (see below) came into existence, separately, in 1949.

The United States, the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union had agreed at Potsdam to a broad program of decentralization, treating Germany as a single economic unit with some central administrative departments. These plans broke down in 1948 with the emergence of the Cold War.

Note: in order to impress the German people with the American opinion of them, a strict non-fraternization policy was initially adhered to by US General Dwight D. Eisenhower and the War department. However, due to pressure from the State Department and individual US congressmen this policy was soon lifted in stages. In June 1945 the prohibition against speaking with German children was made less strict. In July it became possible to speak to German adults in certain circumstances. In September 1945 the whole policy was completely dropped in Austria and Germany. Only the prohibition on marriage between Americans and German or Austrian civilians remained for some time.[2]

Industrial disarmament in western Germany

The initial proposal for the post-surrender policy of the Western powers, the so-called Morgenthau Plan proposed by Henry Morgenthau, Jr., was one of "pastoralization".[3] The Morgenthau Plan, though subsequently ostensibly shelved due to public opposition, influenced occupation policy; most notably through the U.S. punitive occupation directive JCS 1067[4][5] and The industrial plans for Germany[6][2] [3].

'The ”'Level of Industry plans for Germany” were the plans to lower German industrial potential after World War II. At the Potsdam conference, with the U.S. operating under influence of the Morgenthau plan[6], the victorious Allies decided to abolish the German armed forces as well as all munitions factories and civilian industries that could support them. This included the destruction of all ship and aircraft manufacturing capability. Further, it was decided that civilian industries which might have a military potential, which in the modern era of "total war" included virtually all, were to be severely restricted. The restriction of the latter was set to Germany's "approved peacetime needs", which were defined to be set on the average European standard. In order to achieve this, each type of industry was subsequently reviewed to see how many factories Germany required under these minimum level of industry requirements.

The first plan, from 29 March 1946, stated that German heavy industry was to be lowered to 50% of its 1938 levels by the destruction of 1,500 listed manufacturing plants.[7] In January 1946 the Allied Control Council set the foundation of the future German economy by putting a cap on German steel production—the maximum allowed was set at about 5,800,000 tons of steel a year, equivalent to 25% of the prewar production level.[8] The UK, in whose occupation zone most of the steel production was located, had argued for a more limited capacity reduction by placing the production ceiling at 12 million tons of steel per year, but had to submit to the will of the U.S., France and the Soviet Union (which had argued for a 3 million ton limit). Germany was to be reduced to the standard of life it had known at the height of the Great Depression (1932).[9] Car production was set to 10% of prewar levels, etc.[10]

On 2 February 1946, a dispatch from Berlin reported:

| “ | Some progress has been made in converting Germany to an agricultural and light industry economy, said Brigadier General William Henry Draper Jr., chief of the American Economics Division, who emphasized that there was general agreement on that plan.

He explained that Germany’s future industrial and economic pattern was being drawn for a population of 66,500,000. On that basis, he said, the nation will need large imports of food and raw materials to maintain a minimum standard of living. General agreement, he continued, had been reached on the types of German exports — coal, coke, electrical equipment, leather goods, beer, wines, spirits, toys, musical instruments, textiles and apparel — to take the place of the heavy industrial products which formed most of Germany's pre-war exports.[11] |

” |

The first plan was subsequently followed by a number of new ones, the last signed in 1949. By 1950, after the virtual completion of the by the then much watered-out plans, equipment had been removed from 706 manufacturing plants in the west and steel production capacity had been reduced by 6,700,000 tons.[6]

Timber exports from the U.S. occupation zone were particularly heavy. Sources in the U.S. government stated that the purpose of this was the "ultimate destruction of the war potential of German forests."[12] As a consequence of the practiced clear-felling extensive deforestation resulted which could "be replaced only by long forestry development over perhaps a century."[12]

With the beginning of the Cold war, the U.S. policy gradually changed as it became evident that a return to operation of West German industry was needed not only for the restoration of the whole European economy, but also for the rearmament of West Germany as an ally against the Soviet Union. They feared that the poverty and hunger would drive the West Germans to Communism. General Lucius Clay stated "There is no choice between being a communist on 1,500 calories a day and a believer in democracy on a thousand".

In 6 September 1946 United States Secretary of State, James F. Byrnes made the famous speech Restatement of Policy on Germany, also known as the Stuttgart speech, where he amongst other things repudiated the Morgenthau plan-influenced policies and gave the West Germans hope for the future.

Reports such as The President's Economic Mission to Germany and Austria helped to show the U.S. public how bad the situation in Germany really was.

The next improvement came in July 1947, when after lobbying by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Generals Clay and Marshall, the Truman administration finally realized that economic recovery in Europe could not go forward without the reconstruction of the German industrial base on which it had previously had been dependent.[13] In July 1947, President Harry S. Truman rescinded on "national security grounds"[14] the punitive occupation directive JCS 1067, which had directed the U.S. forces in Germany to "take no steps looking toward the economic rehabilitation of Germany." It was replaced by JCS 1779, which instead stressed that "[a]n orderly, prosperous Europe requires the economic contributions of a stable and productive Germany."[15]

The dismantling did however continue, and in 1949 West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer wrote to the Allies requesting that it end, citing the inherent contradiction between encouraging industrial growth and removing factories and also the unpopularity of the policy.[16] (See also Adenauers original letter to Schuman, Ernest Bevins letter to Robert Schuman urging a reconsideration of the dismantling policy.) [4] [5] Support for dismantling was by this time coming predominantly from the French, and the Petersberg Agreement of November 1949 reduced the levels vastly, though dismantling of minor factories continued until 1951.[17] The final limitations on German industrial levels were lifted after the establishment of the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951, though arms manufacture remained prohibited.[18]

French designs

Under the Monnet Plan, France — intent on ensuring that Germany would never again have the strength to threaten it — had beginning in 1945 attempted to gain economic control of the remaining German industrial areas with large coal and mineral deposits; the Rhineland, the Ruhr area and the Saar area (Germany's second largest center of mining and industry, Upper Silesia, had been handed over by the Allies to Poland for occupation at the Potsdam conference and the German population was being forcibly expelled) (see also French proposal regarding the detachment of German industrial regions 8 September 1945). The Ruhr Agreement had been imposed on the Germans as a condition for permitting them to establish the Federal Republic of Germany.[19] (see also the International Authority for the Ruhr (IAR)). French attempts to gain political control of or permanently internationalize the Ruhr were abandoned in 1951 with the West German agreement to pool its coal and steel resources in return for full political control over the Ruhr (see European Coal and Steel Community). With French economic security guaranteed through access to Ruhr coal now permanently ensured France was satisfied. The French attempt to gain economic control over the Saar was temporarily even more successful.

In the speech Restatement of Policy on Germany, held in Stuttgart on 6 September 1946, the United States Secretary of State James F. Byrnes stated the U.S. motive in detaching the Saar from Germany as "The United States does not feel that it can deny to France, which has been invaded three times by Germany in 70 years, its claim to the Saar territory". The Saarland came under French administration in 1947 as the Saar protectorate; but did return to Germany in January 1957 (following a referendum), with economic reintegration with Germany occurring a few years later.

Although not a party to the Potsdam conference where the policy of industrial disarmament had been set, as a member of the Allied Control Council France came to champion this policy since it ensured a weak Germany.

In time the U.S. also came to the conclusion that West Germany should be, carefully, rearmed as a resource in the cold war. In 31 August 1954 the French parliament voted down the treaty that would have established the European Defense Community, a treaty they themselves had proposed in 1950 as a means to contain German revival. The U.S. who wanted to rearm West Germany was furious at the failure of the treaty, but France had come to see the alliance as not in their best interests.

France had instead focused on another treaty also under development. In May 1950 France had proposed the European Coal and Steel Community with the purpose of ensuring French economic security by perpetuating access to German Ruhr coal, but also to show to the U.S. and the UK that France could come up with constructive solutions, as well as to pacify Germany by making it part of an international project.

Germany was eventually allowed to rearm, but under the auspices of the Western European Union, and later NATO.

Dismantling in East Germany

The Soviet Union engaged in a massive dismantling campaign in its occupation zone, much more intensive than that effected by the Western powers. It was realized that this alienated the German workers from the communist cause, but it was decided that the desperate economic situation in the Soviet Union took priority to alliance building. This was the beginning of the split of Germany.

Marshall plan and currency reform

With the Western Allies eventually becoming concerned about the deteriorating economic situation in their "Trizone"; the American Marshall Plan of economic aid was extended to Western Germany in 1948 and a currency reform, which had been prohibited under the previous occupation directive JCS 1067, introduced the Deutsche Mark and halted rampant inflation. Though the Marshall Plan is regarded as playing a key psychological role in the West German recovery, other factors were also significant.[20] Libertarians, particularly, stress the role of Erhard's economic policies, and point out to the detraction of the monetary significance of the Marshall plan that besides simultaneously demanding large reparations payments "the Allies charged the Germans DM7.2 billion annually ($2.4 billion) for their costs of occupying Germany".[21]

The Soviets had not agreed to the currency reform; in March 1948 they withdrew from the four-power governing bodies, and in June 1948 they initiated the Berlin blockade, blocking all ground transport routes between Western Germany and West Berlin. The Western Allies replied with a continuous airlift of supplies to the western half of the city. The Soviets ended the blockade after 11 months.

Reparations to the U.S.

The Allies confiscated intellectual property of great value, all German patents, both in Germany and abroad, and used them to strengthen their own industrial competitiveness by licensing them to Allied companies.[22] Beginning immediately after the German surrender and continuing for the next two years the U.S. pursued a vigorous program to harvest all technological and scientific know-how as well as all patents in Germany. John Gimbel comes to the conclusion, in his book "Science Technology and Reparations: Exploitation and Plunder in Postwar Germany", that the "intellectual reparations" taken by the U.S. and the UK amounted to close to $10 billion.[23][24][25] During the more than two years that this policy was in place, no industrial research in Germany could take place, as any results would have been automatically available to overseas competitors who were encouraged by the occupation authorities to access all records and facilities. Meanwhile thousands of the best German scientists were being put to work in the U.S. (see also Operation Paperclip)

Nutritional levels and famine

For several years following the surrender German nutritional levels were very low, resulting in very high mortality rates. Throughout all of 1945, the U.S. forces of occupation ensured that no international aid reached ethnic Germans.[26] It was directed that all relief went to non-German displaced persons, liberated Allied POWs, and concentration camp inmates.[27] During 1945 it was estimated that the average German civilian in the U.S. and UK occupation zones received 1200 calories a day.[28] Meanwhile non-German Displaced Persons were receiving 2300 calories through emergency food imports and Red Cross help.[29] In early October 1945 the UK government privately acknowledged in a cabinet meeting that German civilian adult death rates had risen to 4 times the pre-war levels and death rates amongst the German children had risen by 10 times the pre-war levels.[28] The German Red Cross was dissolved, and the International Red Cross and the few other allowed international relief agencies were kept from helping Germans through strict controls on supplies and on travel.[27] The few agencies permitted to help Germans, such as the indigenous Caritas Verband, were not allowed to use imported supplies. When the Vatican attempted to transmit food supplies from Chile to German infants the U.S. State Department forbade it.[30] The German food situation became worst during the very cold winter of 1946–1947 when German calorie intake ranged from 1,000–1,500 calories per day, a situation made worse by severe lack of fuel for heating.[31] Meanwhile the Allies were well fed; the average adult calorie intake was; U.S. 3200–3300; UK 2900; U.S. Army 4000.[32] The German infant mortality rate was twice that of other nations in Western Europe until the end of 1948.[33]

Forced labor reparations

As agreed by the Allies at the Yalta conference Germans were used as forced labor as part of the reparations to be extracted. By 1947 it is estimated that 4,000,000 Germans (both civilians and POWs) were being used as forced labor by the U.S., France, the UK and the Soviet Union. German prisoners were for example forced to clear minefields in France and the low countries. By December 1945 it was estimated by French authorities that 2,000 German prisoners were being killed or injured each month in accidents.[34] In Norway the last available casualty record, from 29 August 1945, shows that by that time a total of 275 German soldiers died while clearing mines, while 392 had been injured.[35] Death rates for the German civilians doing forced labor in the Soviet Union ranged between 19% and 39%, depending on category.

Mass rape

Norman Naimark writes in The Russians in Germany: A History of the Soviet Zone of Occupation, 1945–1949 that although the exact number of women and girls who were raped by members of the Red Army in the months preceding and years following the capitulation will never be known, their numbers are likely in the hundreds of thousands, quite possibly as high as the 2,000,000 victims estimate made by Barbara Johr, in "Befreier und Befreite". Many of these victims were raped repeatedly. Naimark states that not only had each victim to carry the trauma with her for the rest of her days, it inflicted a massive collective trauma on the East German nation (the German Democratic Republic). Naimark concludes "The social psychology of women and men in the Soviet zone of occupation was marked by the crime of rape from the first days of occupation, through the founding of the GDR in the fall of 1949, until—one could argue—the present."[36] Some of the victims had been raped as many as 60 to 70 times.[37]

Hostility against Germans

The post-war hostility shown to the German people is exemplified in the fate of the War children, sired by German soldiers with women from the local population in nations such as Norway where the children and their mothers after the war had to endure many years of abuse. In the case of Denmark the hostility felt towards all things German also showed itself in the treatment of German refugees during the years 1945 to 1949. During 1945 alone 7000–10000 German children under the age of 5 died as a result of being denied sufficient food and denied medical attention by Danish doctors who were afraid that rendering aid to the children of the former enemy would be seen as an unpatriotic act. Many children died of easily treatable ailments. As a consequence more German refugees died in Danish camps, "than Danes did during the entire war."[38][39][40][41]

The different German states

- In 1947, the Saar (protectorate) had been established under French control, in the area corresponding to the current German state of Saarland. It was not allowed to join its fellow German neighbors until a plebiscite in 1955 rejected the proposed autonomy. This paved the way for the accession of the Saarland to the Federal Republic of Germany as its 12th state, with effect of 1 January 1957.

- On 23 May 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG, Bundesrepublik Deutschland) was established on the territory of the Western occupied zones, with Bonn as its "provisional" capital. It comprised the area of 11 newly-formed states (replacing the pre-war states), with present-day Baden-Württemberg being split into three states until 1952). The Federal Republic was declared "fully sovereign" on 5 May 1955.

- On 7 October 1949 the German Democratic Republic (GDR, Deutsche Demokratische Republik (DDR)), with East Berlin as its capital, was established in the Soviet Zone.

The 1952 Stalin Note proposed German reunification and superpower disengagement from Central Europe but Britain, France, and the United States rejected the offer as insincere. Also, West German chancellor Konrad Adenauer preferred "Westintegration", rejecting "experiments".

In English the two larger states were known informally as "West Germany" and "East Germany" respectively. In both cases the former occupying troops remained permanently stationed there. The former German capital, Berlin, was a special case, being divided into East Berlin and West Berlin, with West Berlin completely surrounded by East German territory. Though the German inhabitants of West Berlin were citizens of the Federal Republic of Germany, West Berlin was not legally incorporated into West Germany; it remained under the formal occupation of the western allies until 1990, although most day-to-day administration was conducted by an elected West Berlin government.

West Germany was allied with the United States of America, the UK and France. A western capitalist country with a "social market economy", the country would from the 50s onwards come to enjoy prolonged economic growth (Wirtschaftswunder) following the Marshall Plan help from the Allies, the currency reform of June 1948 and helped by the fact that the Korean war (1950–53) led to a worldwide increased demand for goods, where the resulting shortage helped overcome lingering resistance to the purchase of German products.

East Germany was at first occupied by and later (May 1955) allied with the Soviet Union.

West Germany (Federal Republic of Germany)

The Western Allies turned over increasing authority to Western Germany and moved to establish a nucleus for a future German government by creating a central Economic Council for their zones. The program later provided for a West German constituent assembly, an occupation statute governing relations between the Allies and the German authorities, and the political and economic merger of the French with the British and American zones. On 23 May 1949, the Grundgesetz (Basic Law), the constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany, was promulgated. Following elections in August, the first federal government was formed on 20 September 1949, by Konrad Adenauer (CDU). The next day, the occupation statute came into force, granting powers of self-government with certain exceptions.

In 1949 the new provisional capital of the Federal Republic of Germany was established in Bonn, after Chancellor Konrad Adenauer intervened emphatically for Bonn (which was only fifteen kilometers away from his hometown). Most of the members of the German constitutional assembly (as well as the U.S. Supreme Command) had favoured Frankfurt am Main where the Hessian administration had already started the construction of a plenary assembly hall. The Parlamentarischer Rat (interim parliament) proposed a new location for the capital, as Berlin was then a special administrative region controlled directly by the allies and surrounded by the Soviet zone of occupation. The former Reichstag building in Berlin was occasionally used as a venue for sittings of the Bundestag and its committees and the Bundesversammlung, the body which elects the German Federal President. However the Soviets disrupted the use of the Reichstag building by institutions of the Federal Republic of Germany by flying supersonic jets near the building. A number of cities were proposed to host the federal government, and Kassel (among others) was eliminated in the first round. Other politicians opposed the choice of Frankfurt out of concern that, one of the largest German cities and a former centre of the Holy Roman Empire, it would be accepted as a "permanent" capital of Germany, thereby weakening the West German population's support for reunification and the eventual return of the Government to Berlin.

After the Petersberg agreement West Germany quickly progressed toward fuller sovereignty and association with its European neighbors and the Atlantic community. The London and Paris agreements of 1954 restored most of the state's sovereignty (with some exceptions) in May 1955 and opened the way for German membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). In April 1951, West Germany joined with France, Italy and the Benelux countries in the European Coal and Steel Community (forerunner of the European Union).

The outbreak of war in Korea (June 1950) led to U.S. calls for the rearmament of West Germany in order to defend western Europe from the perceived Soviet threat. But the memory of German aggression led other European states to seek tight control over the West German military. Germany's partners in the Coal and Steel Community decided to establish a European Defence Community (EDC), with an integrated army, navy and air force, composed of the armed forces of its member states. The West German military would be subject to complete EDC control, but the other EDC member states (Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands) would cooperate in the EDC while maintaining independent control of their own armed forces.

Though the EDC treaty was signed (May 1952), it never entered into force. France's Gaullists rejected it on the grounds that it threatened national sovereignty, and when the French National Assembly refused to ratify it (August 1954), the treaty died. The French had killed their own proposal. Other means then had to be found to allow West German rearmament. In response, the Brussels Treaty was modified to include West Germany, and to form the Western European Union (WEU). West Germany was to be permitted to rearm, and have full sovereign control of its military; the WEU would however regulate the size of the armed forces permitted to each of its member states. Fears of a return to Nazism, however, soon receded, and as a consequence these provisions of the WEU treaty have little effect today.

West Germany, soon benefiting from the currency reform of 1948 and the Allied Marshall Plan, saw the fastest period of growth in European history from the early 1950s on. Industrial production increased by 35%. Agricultural production substantially surpassed pre-war levels. The poverty and starvation of the immediate postwar years disappeared, and West Germany embarked upon an unprecedented two decades of growth that saw standards of living increase dramatically. This period of time became soon known as the "economic miracle" or Wirtschaftswunder, and is strongly associated with then-Minister of Economy Ludwig Erhard.

The three Western Allies retained occupation powers in Berlin and certain responsibilities for Germany as a whole. Under the new arrangements, the Allies stationed troops within West Germany for NATO defense, pursuant to stationing and status-of-forces agreements. With the exception of 45,000 French troops, Allied forces were under NATO's joint defense command. (France withdrew from the collective military command structure of NATO in 1966.)

Political life in West Germany was remarkably stable and orderly. The Adenauer era (1949–63) was followed by a brief period under Ludwig Erhard (1963–66) who, in turn, was replaced by Kurt Georg Kiesinger (1966–69). All governments between 1949 and 1966 were formed by the united caucus of the Christian-Democratic Union (CDU) and Christian Social Union (CSU), either alone or in coalition with the smaller Free Democratic Party (FDP).

Kiesinger's 1966–69 grand coalition was between West Germany's two largest parties, the CDU/CSU and the Social Democratic Party (SPD). This was important for the introduction of new emergency acts — the grand coalition gave the ruling parties the two-thirds majority of votes required for their ratification. These controversial acts allowed basic constitutional rights such as freedom of movement to be limited in case of a state of emergency.

During the time leading up to the passing of the laws, there was fierce opposition to them, above all by the Free Democratic Party, the rising German student movement, a group calling itself Notstand der Demokratie (Democracy in Crisis) and the labour unions. Demonstrations and protests grew in number, and in 1967 the student Benno Ohnesorg was shot in the head and killed by the police. The press, especially the tabloid Bild-Zeitung newspaper, launched a massive campaign against the protesters and in 1968, apparently as a result, there was an attempted assassination of one of the top members of the German socialist students' union, Rudi Dutschke.

In the 1960s a desire to confront the Nazi past came into being (Frankfurt Auschwitz trials). Successfully, mass protests clamored for a new Germany. Environmentalism and anti-nationalism became fundamental values of West Germany. Rudi Dutschke recovered sufficiently to help establish the Green Party of Germany by convincing former student protesters to join the Green movement. As a result in 1979 the Greens were able to reach the 5% limit required to obtain parliamentary seats in the Bremen provincial election. Dutschke died in 1979 due to the epilepsy he had from the attack.

Another result of the unrest in the 1960s was the founding of the Red Army Faction (RAF) which was active from 1968, carrying out a succession of terrorist attacks in West Germany during the 1970s. Even in the 1990s attacks were still being committed under the name "RAF". The last action took place in 1993 and the group announced it was giving up its activities in 1998.

In the 1969 election, the SPD – headed by Willy Brandt – gained enough votes to form a coalition government with the FDP. Chancellor Brandt remained head of government until May 1974, when he resigned after Günter Guillaume, a senior member of his staff, was uncovered as a spy for the East German intelligence service, the Stasi.

Finance Minister Helmut Schmidt (SPD) then formed a government and received the unanimous support of coalition members. He served as Chancellor from 1974 to 1982. Hans-Dietrich Genscher, a leading FDP official, became Vice Chancellor and Foreign Minister. Schmidt, a strong supporter of the European Community (EC) and the Atlantic alliance, emphasized his commitment to "the political unification of Europe in partnership with the USA".

In October 1982, the SPD-FDP coalition fell apart when the FDP joined forces with the CDU/CSU to elect CDU Chairman Helmut Kohl as Chancellor in a Constructive Vote of No Confidence. Following national elections in March 1983, Kohl emerged in firm control of both the government and the CDU. The CDU/CSU fell just short of an absolute majority, due to the entry into the Bundestag of the Greens, who received 5.6% of the vote.

In January 1987, the Kohl-Genscher government was returned to office, but the FDP and the Greens gained at the expense of the larger parties. Kohl's CDU and its Bavarian sister party, the CSU, slipped from 48.8% of the vote in 1983 to 44.3%. The SPD fell to 37%; long-time SPD Chairman Brandt subsequently resigned in April 1987 and was succeeded by Hans-Jochen Vogel. The FDP's share rose from 7% to 9.1%, its best showing since 1980. The Greens' share rose to 8.3% from their 1983 share of 5.6%.

East Germany (German Democratic Republic)

In the Soviet occupation zone, the Social Democratic Party was forced to merge with the Communist Party in April 1946 to form a new party, the Socialist Unity Party (SED). The October 1946 elections resulted in coalition governments in the five Land (state) parliaments with the SED as the undisputed leader.

A series of people's congresses were called in 1948 and early 1949 by the SED. Under Soviet direction, a constitution was drafted on 30 May 1949, and adopted on 7 October, the day when East Germany was formally proclaimed. The People's Chamber (Volkskammer) – the lower house of the East German parliament – and an upper house – the States Chamber (Länderkammer) – were created. (The Länderkammer was abolished again in 1958.) On 11 October 1949, the two houses elected Wilhelm Pieck as President, and an SED government was set up. The Soviet Union and its East European allies immediately recognized East Germany, although it remained largely unrecognised by non-communist countries until 1972-73. East Germany established the structures of a single-party, centralized, communist state. On 23 July 1952, the traditional Länder were abolished and, in their place, 14 Bezirke (districts) were established. Even though other parties formally existed, effectively, all government control was in the hands of the SED, and almost all important government positions were held by SED members.

The National Front was an umbrella organization nominally consisting of the SED, four other political parties controlled and directed by the SED, and the four principal mass organizations – youth, trade unions, women, and culture. However, control was clearly and solely in the hands of the SED. Balloting in East German elections was not secret. As in other Soviet bloc countries, electoral participation was consistently high, with nearly unanimous candidate approval.

Berlin

Shortly after World War II, Berlin became the seat of the Allied Control Council, which was to have governed Germany as a whole until the conclusion of a peace settlement. In 1948, however, the Soviet Union refused to participate any longer in the quadripartite administration of Germany. They also refused to continue the joint administration of Berlin and drove the government elected by the people of Berlin out of its seat in the Soviet sector and installed a communist regime in East Berlin. From then until unification, the Western Allies continued to exercise supreme authority—effective only in their sectors—through the Allied Kommandatura. To the degree compatible with the city's special status, however, they turned over control and management of city affairs to the West Berlin Senate (executive) and House of Representatives, governing bodies established by constitutional process and chosen by free elections. The Allies and German authorities in West Germany and West Berlin never recognized the communist city regime in East Berlin or East German authority there.

During the years of West Berlin's isolation—176 kilometres (110 mi.) inside East Germany—the Western Allies encouraged a close relationship between the Government of West Berlin and that of West Germany. Representatives of the city participated as non-voting members in the West German Parliament; appropriate West German agencies, such as the supreme administrative court, had their permanent seats in the city; and the governing mayor of West Berlin took his turn as President of the Bundesrat. In addition, the allies carefully consulted with the West German and West Berlin Governments on foreign policy questions involving unification and the status of Berlin.

Between 1948 and 1990, major events such as fairs and festivals were sponsored in West Berlin, and investment in commerce and industry was encouraged by special concessionary tax legislation. The results of such efforts, combined with effective city administration and the West Berliners' energy and spirit, were encouraging. West Berlin's morale was sustained, and its industrial production considerably surpassed the pre-war level.

The Final Settlement Treaty ended Berlin's special status as a separate area under Four Power control. Under the terms of the treaty between West and East Germany, Berlin became the capital of a unified Germany. The Bundestag voted in June 1991 to make Berlin the seat of government. The Government of Germany asked the allies to maintain a military presence in Berlin until the complete withdrawal of the Western Group of Forces (ex-Soviet) from the territory of the former East Germany. The Russian withdrawal was completed 31 August 1994. Ceremonies were held on 8 September 1994, to mark the final departure of Western Allied troops from Berlin.

Government offices have been moving progressively to Berlin, and it became the formal seat of the federal government in 1999. Berlin also is one of the Federal Republic's 16 Länder.

Relations between East and West Germany

Under Chancellor Adenauer West Germany declared its right to speak for the entire German nation with an exclusive mandate. The Hallstein Doctrine involved non-recognition of East Germany, and restricted (or often ceased) diplomatic relations to countries that gave East Germany the status of a sovereign state.

The constant stream of East Germans fleeing across the Inner German border to West Germany placed great strains on East German-West German relations in the 1950s. East Germany sealed the borders to West Germany in 1952, but people continued to flee from East Berlin to West Berlin. On 13 August 1961, East Germany began building the Berlin Wall around West Berlin to slow the flood of refugees to a trickle, effectively cutting the city in half and making West Berlin an enclave of the Western world in communist territory. The Wall became the symbol of the Cold War and the division of Europe. Shortly afterwards, the main border between the two German states was fortified.

The Letter of Reconciliation of the Polish Bishops to the German Bishops of 1965 was controversial at the time, but is now seen as an important step toward improving relations between the German states and Poland.

In 1969, Chancellor Willy Brandt announced that West Germany would remain firmly rooted in the Atlantic alliance but would intensify efforts to improve relations with Eastern Europe and East Germany. West Germany commenced this Ostpolitik, initially under fierce opposition from the conservatives, by negotiating non-aggression treaties with the Soviet Union, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, and Hungary.

West Germany's relations with East Germany posed particularly difficult questions. Though anxious to relieve serious hardships for divided families and to reduce friction, West Germany under Brandt's Ostpolitik was intent on holding to its concept of "two German states in one German nation." Relations gradually improved. In the early 1970s, Ostpolitik led to a form of mutual recognition between East and West Germany. The Treaty of Moscow (August 1970), the Treaty of Warsaw (December 1970), the Four Power Agreement on Berlin (September 1971), the Transit Agreement (May 1972), and the Basic Treaty (December 1972) helped to normalise relations between East and West Germany and led to both states joining the United Nations, in September 1973. The two German states exchanged permanent representatives in 1974, and, in 1987, East German head of state Erich Honecker paid an official visit to West Germany.

The reunification of East and West Germany

Background

International plans for the unification of Germany were made during the early years following the establishment of the two states, but to no avail. In March 1952, the Soviet government proposed the Stalin Note to hold elections for a united German assembly while making the proposed united Germany a neutral state, i.e. a neutral state approved by the people, similar to the Austrians' approval of a neutral Austria. The Western Allied governments refused this initiative, while continuing West Germany's integration into the western alliance system. The issue was raised again during the Foreign Ministers' Conference in Berlin in January–February 1954, but the western powers refused to make Germany neutral. Following Bonn's adherence to NATO on 9 May 1955, such initiatives were abandoned by both sides.

During the summer of 1989, rapid changes took place in East Germany, which ultimately led to German reunification. Widespread discontent boiled over, following accusations of large scale vote-rigging during the local elections of May 1989. Growing numbers of East Germans emigrated to West Germany via Hungary after the Hungarians decided not to use force to stop them. Thousands of East Germans also tried to reach the West by staging sit-ins at West German diplomatic facilities in other East European capitals. The exodus generated demands within East Germany for political change, and mass demonstrations with eventually hundreds of thousands of people in several cities – particularly in Leipzig – continued to grow. On 7 October, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev visited Berlin to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the establishment of East Germany and urged the East German leadership to pursue reform, without success.

On 18 October, Erich Honecker was forced to resign as head of the SED and as head of state and was replaced by Egon Krenz. But the exodus continued unabated, and pressure for political reform mounted. On November 4, a demonstration in East Berlin drew as many as 1 million East Germans. Finally, on 9 November 1989, the Berlin Wall was opened, and East Germans were allowed to travel freely. Thousands poured through the wall into the western sectors of Berlin, and on November 12, East Germany began dismantling it.

On 28 November, West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl outlined a 10-point plan for the peaceful unification of the two German states, based on free elections in East Germany and a unification of their two economies. In December, the East German Volkskammer eliminated the SED monopoly on power, and the entire Politbüro and Central Committee – including Krenz – resigned. The SED changed its name to the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS) and the formation and growth of numerous political groups and parties marked the end of the communist system. Prime Minister Hans Modrow headed a caretaker government which shared power with the new, democratically oriented parties. On 7 December 1989, agreement was reached to hold free elections in May 1990 and rewrite the East German constitution. On 28 January, all the parties agreed to advance the elections to 18 March, primarily because of an erosion of state authority and because the East German exodus was continuing apace; more than 117,000 left in January and February 1990.

In early February 1990, the Modrow government's proposal for a unified, neutral German state was rejected by Chancellor Kohl, who affirmed that a unified Germany must be a member of NATO. Finally, on 18 March , the first free elections were held in East Germany, and a government led by Lothar de Maizière (CDU) was formed under a policy of expeditious unification with West Germany. The freely elected representatives of the Volkskammer held their first session on 5 April, and East Germany peacefully evolved from a communist to a democratically elected government. Free and secret communal (local) elections were held in the GDR on 6 May, and the CDU again won most of the available seats. On 1 July, the two German states entered into an economic and monetary union.

Treaty negotiations

During 1990, in parallel with internal German developments, the Four Powers – the Allies of World War II, being the United States, United Kingdom, France, and the Soviet Union – together with the two German states negotiated to end Four Power reserved rights for Berlin and Germany as a whole. These "Two-plus-Four" negotiations were mandated at the Ottawa Open Skies conference on 13 February 1990. The six foreign ministers met four times in the ensuing months in Bonn (5 May), Berlin (22 June), Paris (17 July), and Moscow (12 September). The Polish Foreign Minister participated in the part of the Paris meeting that dealt with the Polish-German borders.

Of key importance was overcoming Soviet objections to a united Germany's membership in NATO. This was accomplished in July when the alliance, led by President George H.W. Bush, issued the London Declaration on a transformed NATO. On 16 July, President Gorbachev and Chancellor Kohl announced agreement in principle on a united Germany in NATO. This cleared the way for the signing in Moscow, on 12 September, of the Treaty on the Final Settlement With Respect to Germany – in effect the peace treaty that was anticipated at the end of World War II. In addition to terminating Four Power rights, the treaty mandated the withdrawal of all Soviet forces from Germany by the end of 1994, made clear that the current borders (especially the Oder-Neisse line) were viewed as final and definitive, and specified the right of a united Germany to belong to NATO. It also provided for the continued presence of British, French, and American troops in Berlin during the interim period of the Soviet withdrawal. In the treaty, the Germans renounced nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons and stated their intention to reduce the (combined) German armed forces to 370,000 within 3 to 4 years after the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe, signed in Paris on 19 November 1990, entered into force.

Conclusion of the final settlement cleared the way for unification of East and West Germany. Formal political union occurred on 3 October 1990, executed – not without criticism – via Article 23 of West Germany's Basic Law as the accession of the restored five eastern Länder (meaning that technically, East Germany was subsumed into West Germany). On 2 December 1990, all-German elections were held for the first time since 1933. The "new" country stayed the same as the West German legal system and institutions were extended to the east. The unified nation kept the name Bundesrepublik Deutschland (though the simple 'Deutschland' would become increasingly common) and retained the West German "Deutsche Mark" for currency as well. Berlin would formally become the capital of the united Germany, but the political institutions remained at Bonn for the time being. Only after a heated 1991 debate did the Bundestag conclude on moving itself and most of the government to Berlin as well, a process that took until 1999 to complete, when the Bundestag held its first session at the reconstructed Reichstag building. Many government departments still maintain sizable presences in Bonn as of 2008.

Aftermath

To this day, there remain vast differences between the former East Germany and West Germany (for example, in lifestyle, wealth, political beliefs and other matters) and thus it is still common to speak of eastern and western Germany distinctly. The eastern German economy has struggled since unification, and large subsidies are still transferred from west to east.

References

- ↑ An instrument of surrender was signed 7 May 1945 in Rheims and the surrender was ratified in Berlin 8 May 1945

Beevor, Antony (2003) [2002]. Berlin: The Downfall 1945. Penguin. pp. 402 ff. ISBN 0-140-28696-9. - ↑ Perry Biddiscombe "Dangerous Liaisons: The Anti-Fraternization Movement in the US Occupation Zones of Germany and Austria, 1945–1948", Journal of Social History 34.3 (2001) p. 619

- ↑ Henry Morgenthau, Jr. (memo initialed by Roosevelt in September 1944). "Memo entitled "Suggested Post-Surrender Program for Germany", signed Henry Morgenthau Jr.". President's Secretary's Files (PSF), German Diplomatic Files, Jan.–Sept. 1944 (i297). Franklin D. Roosevelt Digital Archives. http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/psf/box31/a297a01.html. Retrieved 2007-01-21. "It should be the aim of the Allied Forces to accomplish the complete demilitarization of Germany in the shortest possible period of time after surrender. This means completely disarming the German Army and people (including the removal or destruction of all war material), the total destruction of the whole German armament industry, and the removal or destruction of other key industries which are basic to military strength. [. . .] Within a short period, if possible not longer than 6 months after the cessation of hostilities, all industrial plants and equipment not destroyed by military action shall either be completely dismantled and removed from the [Ruhr] area or completely destroyed. All equipment shall be removed from the mines and the mines shall be thoroughly wrecked."

- ↑ Michael R. Beschloss, "The Conquerors: Roosevelt, Truman and the Destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1941–1945", pg. 233

- ↑ Vladimir Petrov, "Money and conquest; allied occupation currencies in World War II". Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Press (1967) pg. 228–229

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Frederick H. Gareau "Morgenthau's Plan for Industrial Disarmament in Germany" The Western Political Quarterly, Vol. 14, No. 2 (Jun., 1961), pp. 517–534

- ↑ Henry C. Wallich. Mainsprings of the German Revival (1955) pg. 348.

- ↑ "Cornerstone of Steel", Time Magazine, January 21, 1946

- ↑ Cost of Defeat, Time Magazine, 8 April 1946

- ↑ The President's Economic Mission to Germany and Austria, Report 3 Herbert Hoover, March, 1947 pg. 8

- ↑ James Stewart Martin. All Honorable Men (1950) pg. 191.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Nicholas Balabkins, "Germany Under Direct Controls; Economic Aspects Of Industrial Disarmament 1945–1948, Rutgers University Press, 1964. p. 119. The two quotes used by Balabkins are referenced to respectively; U.S. office of Military Government, A Year of Potsdam: The German Economy Since the Surrender (1946), p.70; and U.S. Office of Military Government, The German Forest Resources Survey (1948), p. II. For similar observations Balabkins also directs the reader in the footnotes to G.W. Harmssen, Reparationen, Sozialproduct, Lebensstandard (Bremen: F. Trujen Verlag, 1948), I, 48.

- ↑ Ray Salvatore Jennings "The Road Ahead: Lessons in Nation Building from Japan, Germany, and Afghanistan for Postwar Iraq May 2003, Peaceworks No. 49 pg.15

- ↑ Ray Salvatore Jennings “The Road Ahead: Lessons in Nation Building from Japan, Germany, and Afghanistan for Postwar Iraq May 2003, Peaceworks No. 49 pg.15

- ↑ Pas de Pagaille! Time Magazine July 28, 1947.

- ↑ Dennis L. Bark and David R. Gress. A history of West Germany vol 1: from shadow to substance (Oxford 1989) p259

- ↑ Dennis L. Bark and David R. Gress. A history of West Germany vol 1: from shadow to substance (Oxford 1989) p260

- ↑ Dennis L. Bark and David R. Gress. A history of West Germany vol 1: from shadow to substance (Oxford 1989) pp. 270–71

- ↑ Amos Yoder, "The Ruhr Authority and the German Problem", The Review of Politics, Vol. 17, No. 3 (Jul., 1955), pp. 345–358

- ↑ Stern, Susan (2001, 2007). "Marshall Plan 1947–1997 A German View". Germany Info. German Embassy's Department for Press, Information and Public Affairs, Washington D.C. http://www.germany.info/relaunch/culture/history/marshall.html. Retrieved 2007-05-03. "There is another reason for the Plan's continued vitality. It has transcended reality and become a myth. To this day, a truly astonishing number of Germans (and almost all advanced high school students) have an idea what the Marshall Plan was, although their idea is very often very inaccurate. [. . .] Many Germans believe that the Marshall Plan was alone responsible for the economic miracle of the Fifties. And when scholars come along and explain that reality was far more complex, they are skeptical and disappointed. They should not be. For the Marshall Plan certainly did play a key role in Germany's recovery, albeit perhaps more of a psychological than a purely economic one."

- ↑ Henderson, David R. (1993, 2002). "German Economic "Miracle"". The Concise Encyclopaedia of Economics. The Library of Economics and Liberty. http://www.econlib.org/library/enc/GermanEconomicMiracle.html. Retrieved 2007-05-03. "This account has not mentioned the Marshall Plan. Can't the German revival be attributed mainly to that? The answer is no. The reason is simple: Marshall Plan aid to Germany was not that large. Cumulative aid from the Marshall Plan and other aid programs totaled only $2 billion through October 1954. Even in 1948 and 1949, when aid was at its peak, Marshall Plan aid was less than 5 percent of German national income. Other countries that received substantial Marshall Plan aid had lower growth than Germany. Moreover, while Germany was receiving aid, it was also making reparations and restitution payments that were well over $1 billion. Finally, and most important, the Allies charged the Germans DM7.2 billion annually ($2.4 billion) for their costs of occupying Germany."

- ↑ C. Lester Walker "Secrets By The Thousands", Harper's Magazine. October 1946

- ↑ Norman M. Naimark The Russians in Germany pg. 206. (Naimark refers to Gimbels book)

- ↑ The $10 billion compares to the U.S. annual GDP of $258 billion in 1948.

- ↑ The $10 billion compares to the total Marshall plan expenditure (1948–1952) of $13 billion, of which Germany received $1,4 billion (partly as loans).

- ↑ Steven Bela Vardy and T. Hunt Tooley, eds. Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe ISBN 0-88033-995-0. subsection by Richard Dominic Wiggers, “The United States and the Refusal to Feed German Civilians after World War II” pg. 281

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Richard Dominic Wiggers pg. 281–282

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Richard Dominic Wiggers pg. 280

- ↑ Richard Dominic Wiggers pg. 279

- ↑ Richard Dominic Wiggers pg. 281

- ↑ Richard Dominic Wiggers p. 244

- ↑ Richard Dominic Wiggers p. 285

- ↑ Richard Dominic Wiggers pg. 286

- ↑ S. P. MacKenzie "The Treatment of Prisoners of War in World War II" The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 66, No. 3. (Sep., 1994), pp. 487–520.

- ↑ Tjersland, Jonas (2006-04-08). "Tyske soldater brukt som mineryddere (Translation from Norwegian: German soldiers used for mine-clearing)". VG Nett. http://www.vg.no/pub/vgart.hbs?artid=166207. Retrieved 2007-06-02.

- ↑ Norman M. Naimark. The Russians in Germany: A History of the Soviet Zone of Occupation, 1945–1949. Harvard University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-674-78405-7 pp. 132,133

- ↑ William I. Hitchcock The Struggle for Europe The Turbulent History of a Divided Continent 1945 to the Present ISBN 978-0-385-49799-2 (0-385-49799-7)

- ↑ "Danish Study Says German Children Abused". Deutsche Welle. 2005-04-10. http://www.dw-world.de/dw/article/0,1564,1545676,00.html. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ↑ Osborn, Andrew (2003-02-09). "Documentary forces Danes to confront past". History News Network. http://hnn.us/comments/8391.html. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ↑ "Children were starved in war aftermath". New historical research opens a black chapter in the history of Danish conduct during World War II. The Copenhagen Post. 2005-04-15. http://www.cphpost.dk/get/87301.html. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ↑ Ertel, Manfred (2005-05-16). "A Legacy of Dead German Children". Denmarks' myths shattered. Spiegel Online. http://www.spiegel.de/international/0,1518,355772,00.html. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- Fulbrook, Mary. [6]"The Two Germanies, 1945–90" (ch. 7) and "The Federal Republic of Germany Since 1990" (ch. 8) in A Concise History of Germany (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004): 203–249; 249–257.

- Jean Edward Smith, Germany Beyond The Wall: People, Politics, and Prosperity, Boston: Little, Brown, & Company, 1969.

- Jean Edward Smith, Lucius D. Clay: An American Life, New York: Henry, Holt, & Company, 1990.

- Jean Edward Smith, The Defense Of Berlin, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1963.

- Jean Edward Smith, The Papers Of Lucius D. Clay, 2 Vols., Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1974.

- David H Childs, Germany in the Twentieth Century, (From pre-1918 to the restoration of German unity), Batsford, Third edition, 1991. ISBN 0 713467959

- David H Childs and Jeffrey Johnson, West Germany: Politics And Society, Croom Helm, 1982. ISBN 0709907028

- David H Childs, The Two Red Flags: European Social Democracy & Soviet Communism Since 1945, Routledge, 2000. [7]

External links

- Germany at the onset of the cold war

- James F. Byrnes, Speaking Frankly (The division of Germany)

- The President's Economic Mission to Germany and Austria, Report No. 1 (1947)

- The President's Economic Mission to Germany and Austria, Report 3 (1947)

- Contemporary History maintained by the Institute for Contemporary Historical Research in Potsdam (German)

- Special German series 2. The Committee on Dismemberment of Germany Allied discussions on the dismemberment of Germany into separate states, March 29, 1945.

- The overlooked majority: German women in the four zones of occupied Germany, 1945-1949, a comparative study

- East Berlin, Past and Present

- Germany Under Reconstruction is a digital collection that provides a varied selection of publications in both English and German from the period immediately following World War II. Many are publications of the U.S. occupying forces, including reports and descriptions of efforts to introduce U.S.-style democracy to Germany. Some of the other books and documents describe conditions in a country devastated by years of war, efforts at political, economic and cultural development, and the differing perspectives coming from the U.S. and British zones and the Russian zone of occupation.